Boerboel a Dogue De Bordeaux Puppy Stock Photo Image of grass

Below are a few quick comparisons between the two breeds. Owner Experience - Neither the Dogue De Bordeaux or the Boerboel are ideal for new owners but the Boerboel is

Below are a few quick comparisons between the two breeds. Owner Experience - Neither the Dogue De Bordeaux or the Boerboel are ideal for new owners but the Boerboel is

Na szczęście bukszpan łatwo i tanio rozmnożysz z sadzonek które przygotujesz własnoręcznie. Bukszpan można też uprawiać w donicach i formować z niego różne kształty - np. kule. Zobacz jak własnoręcznie

Ruff Cycles Hurricane Rower Miejski Custom Cruiser Ape Hanger. 5 500 zł. Nowe. Oleśnica Oleśnica - 03 grudnia 2023. Wielokolorowy.

Her somber self-empowerment song No One reached No. 6 on the U.S. Viral Spotify Charts. Soon after she released the hit Clear with Canadian producer Pusher; it has earned more

Ranking tanich maszyn do szycia. Opcja budżetowa potrzebna na już? Nie ma problemu. Mamy dla Ciebie również ranking tanich maszyn do szycia. Pamiętaj tylko że naprawdę tania mała maszyna do

Golonka z indyka pieczona to wspaniała propozycja na pyszny obiad. Golonka z indyka zawiera mniejszą ilość kalorii oraz tłuszczu niż tradycyjna wieprzowa golonka. Koniecznie wypróbuj nasz przepis. Składniki dla 5

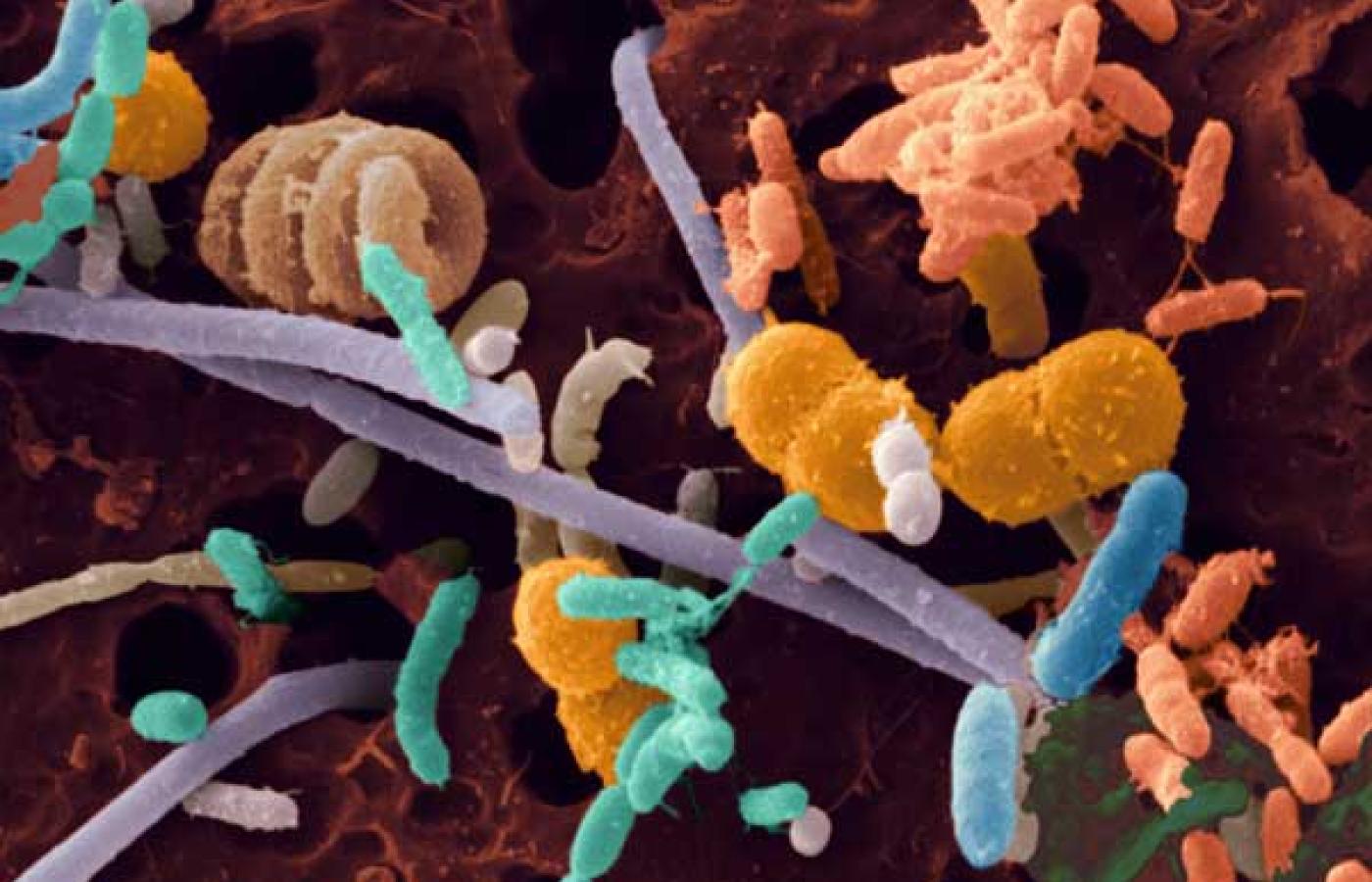

Reducenci to przede wszystkim bakterie i grzyby zwykle żyjące na odchodach lub martwej ściółce na martwych roślinach i zwierzętach a także w układzie trawiennym zwierząt (jako symbionty ). Dzięki działalności

Kup Ozdoby do Kuchni w Dekoracje i ozdoby - Dom i Ogród - Najwięcej ofert w jednym miejscu. Radość zakupów i 100% bezpieczeństwa dla każdej transakcji.. Produkt: DEKORACJA DO KUCHNI

Owczarek belgijski to prawdziwy okaz psiej siły uroku i inteligencji. Jest pełen energii chociaż doskonale rozumie dyscyplinę. Dlaczego hodowle owczarków belgijskich są tak oblegane czy wszystkie psy są takie same